We All Need A Madness

An Interview with Sharda Harrison

by Marc Nair, 9 April 2017

Sharda Harrison sits across from me at a café in Goodman Arts Centre. It’s early, so early the café hasn’t opened, but she’s bright-eyed and full of zest. It’s amazing to see how far she’s come in the seven or so years since we first met and worked together. And it’s fitting that we’re meeting here at Goodman, where she is in rehearsals for Tropicana: The Musical, as this was where we had our first major collaboration, The City Limits, as part of Lit Up 2011.

She tells me that she’s never seen anything like that ever since, and I agree. The City Limits was a devised, collaborative, multidisciplinary show that brought together diverse artists from all disciplines. The process of ideation probably took longer than rehearsals, but that creative canvas is something that Sharda treasures, and which can be seen today in her own intercultural theatre outfit, Pink Gajah.

When was the moment you wanted to become an artist?

I was put in ballet class when I was young, and I loved it and did really well but I didn’t really enjoy it and eventually I forced my mother to sign me up for drama class. But my real defining moment was when Chandran from Act 3 put me in a show called James and the Giant Peach. I was 12 and played a grasshopper. But I was on stage, and I felt that this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. My other turning point was deciding to go to LaSalle and not junior college after my O-Levels. The third point was standing on a cliff in Denmark with a bunch of women and watching a site-specific show. And one of them told me, “Now it’s time to unlearn everything, because a new journey begins."

Right now, I’m most connected theatrically and spiritually to Haresh Sharma and Jo Kokuthas. But my parents are still my biggest life mentors. They’re both mad, by the way.

But we all need a madness to get us somewhere. My father joined the zoo when he was 21, moving up to become the CEO. He was forward thinking, creating an open zoo. Most zoos are run like corporations, but my father was one of the rare ones; a zoologist, and not a suit.

My mother is a Piscean, completely flowy and erratic. She was an aromatherapist, air stewardess, horticulturist, property agent, insurance agent, jamu expert, and more. When I was young she told me I was a child of the universe, there’s no such thing as religion. It’s all free love.

I come from polarities of science and faith. If I’m rolling around in mud for an hour, my father won’t get it. But my mother will see snails, love, women and birth.

I like to push boundaries in my art, but also to rationalise. I’ve taken an aspect of conservation from my father, and this emerged in my show ‘Bicara’ and its earlier incarnation: ‘Why We Do What We Do.’ It came out of my father’s talk on why we treat animals so badly and is a history of men’s behaviour and actions. The show wasn’t just meant for high art but also for a wider audience. What I enjoyed was taking scientific facts and creating characters and narratives with it. I was happy with the process, with work that reaches to people who don’t mind that I am rolling around in mud, being an animal in captivity.

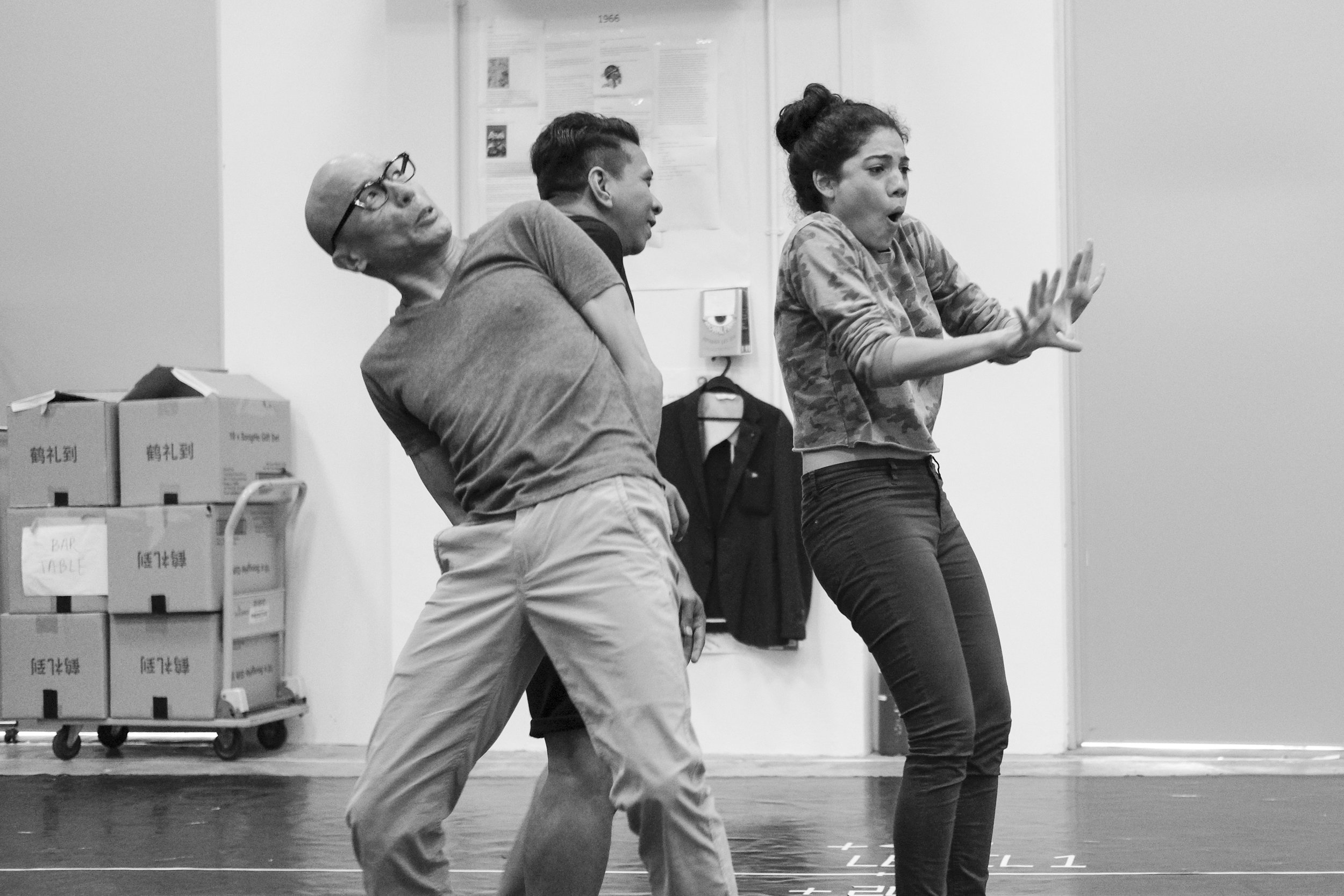

With every show I get, my roles get more challenging. I knew Tropicana was going to be difficult because I don’t sing, and the role wasn’t easy. But my most difficult role was when I had to play a grandmother, Sharifah, in Hotel (Wild Rice - 2015,2016). So I played the young Sharifah who was the lover of a Japanese soldier in WW2 and an older version, 40 years later, just ten minutes apart. And I have to play from contrasting emotions, and speak in Malay! But it reminded me of my grandmother’s own story, so I did find some empathy in that. My grandmother was forced to marry a Japanese man, who left her and their child when the war broke out. It left my grandmother in such a state that if you mention the word ‘sushi’ she would scream.

I saw this role as my grandmother’s role, so in a way there’s a shamanistic element. I would feel a lot of things before I entered the role, and therefore the character kept revealing new facets every night. So I continually discovered new things that hurt, but also brought me great joy.

Whatever we do on stage reflects in life, and if that doesn’t happen than I don’t think the art is good enough. Because the energy that needs to be created on stage needs to keep transitioning and evolving, otherwise it becomes one-dimensional.

Tell me about Tropicana.

Tropicana is about the anger of society in Singapore between the ‘60s to the ‘80s. It was years of immense social and political change. There’s a potent, latent anger in this era, but it’s also about the people of Singapore and how we dealt with prohibition, anti-yellow culture. This is a generation of nostalgia, a moment of time that many of us weren’t around for. Those who were remember it as a happy memory.

Tropicana was a symbol. We had a place for topless dancing that doesn’t exist anymore! It’s quite telling.

Sharda Harrison as Pinky the showgirl. Photo credit: www.tropicanathemusical.com