SECULAR MISSIONARIES: AN INTERVIEW WITH UNITY IN HEALTH

by Marc Nair, 9 Dec 2018

The need for the NGO is highly questionable if society functions as it is supposed to. It rises as a companion to the expansionist dreams of capitalist economies and is often a scion of wars and economic devastation, entering like show ponies of Western sympathy or, as Arundhati Roy so aptly puts it, "secular missionaries of the modern world.” (Roy, The NGO-ization of Resistance)

But not all NGOs are riddled with scandals or are fronts for volun-tourism. I was fortunate to sit down with Gayathri Santhi-McBain and João Marçal-Grilo of Unity in Health to find out more about the important work they do in building for long-term sustainability and self-sufficiency.

Gayathri Santhi-McBain and João Marçal-Grilo planning the next phase of their outreach.

Photo by Mackerel.

Who is Unity in Health and what kind of work do you do?

We’re a four year old NGO, small but eclectic. Our staff comes from a mental health background. We have four trustees from different backgrounds and Gaythri is one of them. We work towards supporting our colleagues who work in mental healthcare in low-income countries through training and developmental programs.

Gayathri co-facilitating a training session for healthcare assistants at KOSHISH Nepal. Kathmandu, Nov 2017.

How has Unity in Health been working with communities in developing countries?

We work in Sri Lanka and Nepal. There’s a lot of similarities between these two countries. They’re both quite small but contain a huge diversity in terms of ethnic and religious groups, which gives us a sample of what goes on in South Asia.

But bureaucracy made it difficult to get things going in Sri Lanka, and so we moved to Nepal, where our initiatives got off the ground immediately. The needs are greater in Nepal, and overall, people are poorer. But now that we’ve built a strong portfolio in Nepal, we hope to go back to Sri Lanka to reconnect and restart our projects.

We feel there’s a lot to learn about how local healthcare deals with mental illness, particularly when you compare it to a place like London which is very diverse. But, for example, we can learn how to take the way Nepalese deal with stigma to reach out to underserved communities in London.

What is your workflow like?

We don’t want to impose our Western ways, but want to create a flow and exchange of ideas all across the world. Up to now we’ve had volunteers from abroad come to Sri Lanka and Nepal, but we are working on getting two psychiatrists from Nepal to come to London to be exposed to areas of clinical care and also to share their experience of clinical care with doctors who serve the Nepali community in London. It’s about finding the appropriate placements.

Training programme by Unity in Health for the nursing staff of the Nepal Medical College

We very much want to involve local authorities in whatever we do. We don’t just want to deliver vaccines or operate short-term, where no self-sufficiency or independence is created or given to the locals. It’s not just about filling the gaps, but about working together to give them accountability and shared responsibility so that long-term sustainability is possible. We want to empower people on the ground and reduce our involvement to a minimum.

How are you empowering women (whom I imagine are the bulk of the healthcare professionals you work with)?

One of the central principles of Unity in Health is to effect change for women in South Asia. Nursing is a very female-centred profession, so this gives us a chance to raise the skill level of the community and give them financial and professional independence.

We’ve also been approached by the University of Islamabad in Pakistan to run a training course for general nurses on basic mental and emotional healthcare needs. And to go to Peshwara to work with nurses who are on the frontline as carers and deliverers of help for mental health needs.

UiH’s training programme for nurses at the Nepal Medical College

In Nepal, we also want to enable nurses to be able to shape mental health issues in the country. Right now, it’s male doctors who make all the decisions. The doctor is heralded as the pinnacle of the medical community and there’s a level of deference and subservience even in an advanced healthcare system such as the NHS. You need a particular type of doctor who is willing to get rid of his God complex and acknowledge that in many cases the nurses run the show.

What differentiates Unity in Health from other medical NGOs?

When you see Western NGOs, their approach and attitude tends to be skewed, but we are very aware that we need to understand the sensitivities of a particular community. So we don’t go in with a huge budget and high hopes but we are nimble and small and therefore able to adapt and meet local needs. For example, we have an Occupational Therapist course in Sri Lanka that doesn’t exist in Nepal, so we hope to get trained Occupational Therapists from Sri Lanka to come to Nepal to start a course.

What challenges do UiH staff face on the ground?

Mental health issues, even suicide, are becoming more prevalent amongst 12-13 year old schooling girls in Nepal, and we feel that they don’t have role models, so they don’t know where they will end up. They don’t have positive examples of women who have gone through the school system. So we see this as a gap where we can step in to build mental health programmes.

How empowered have the locals been from UiH’s efforts?

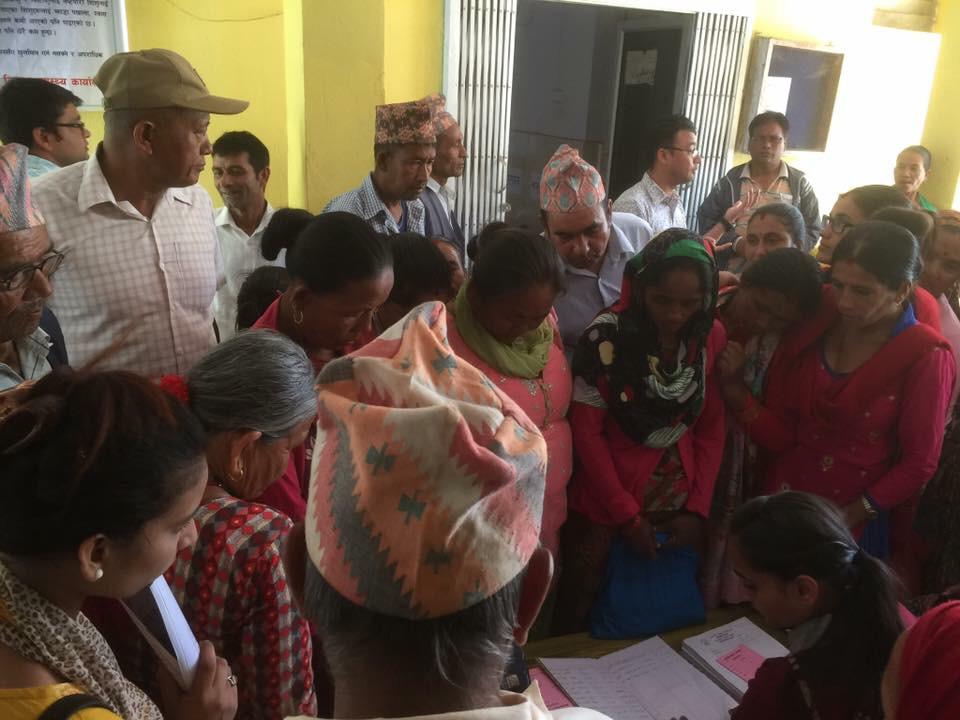

Something we’ve been doing of late is community outreach in the form of a mobile mental health clinic which brings care to remote areas of Nepal, as most of the care is concentrated in the capital, Kathmandu. We put a local team together and provided them with the resources they need to facilitate those clinics. And we’re starting to research how that care can better be provided and how we can build relationships with local authorities so that the government can get onboard and replicate our programmes.

So we’ll be heading to Ilam in East Nepal, about 30 hours from Kathmandu, to set up a mobile clinic on a hill and get volunteers to radio out to villages that the clinic is here.

But what does a mental mobile clinic look like?

One of the problems we’ve been having is that previous clinics were one-offs, so people were being seen once every two years. So people walked for hours to get to a clinic, but ended up not being treated properly. But now we have the funds, we are going to try to go once a month. The last time I was there, there was one doctor and one psychologist seeing about 120 people over one day. Each person was attended to for between 2 to 5 minutes. It was chaos. There was no confidentiality. And you also see people with physical health problems.

So you almost need triage.

Definitely. So the volunteers and the radio programmes encourage the right people to come. But if you’re in the middle of nowhere and you know there’s going to be a doctor in town… We saw all kinds of people. There was a seven year old girl who was kept in a cage because her grandmother had to work. Her brother was sent to school, but she was put in a cage.

A lot of the work we did was simply to talk to the team and ask them, “How could we do things differently?” So some things we’ll change is to be there for four days, and not one. And to see each patient for at least fifteen minutes. We’re going to work with local volunteers to help patients order medicine, so they can continue their treatment. We don’t sit with the patients but we encourage reflection from the healthcare staff. And we’ve been fundraising to empower them with necessary resources. Our long-term plan is to develop a model that appeals to the local authorities so they will continue with the program after we have left. We also hope to develop an online platform in Nepali to invite celebrities to post and share their experience. A kind of virtual helpline.

Like a portal with videos and a forum?

Exactly. Initially we wanted to do a radio program. But we realised there are already 4 existing radio programs on mental health! And this will make it far more interactive. We want to make mental health something that people we talk about. Not just in Nepal, but globally, we need a shift. Even Michael Phelps has come out to talk about his struggles with depression.

Who else do you work with in the field?

One of our partner organisations is Chora chori, which translates as ‘sons and daughters’. They rescue Nepali children who have been trafficked into India. In some cases they are runaways, or they have been sold by their parents.

When you say rescue, do you mean like in the movies?

Have you seen the movie Leon? It’s exactly like that. Chora Chori go to homes in the state of Bihar, one of the poorest states in India. Most of the children have been found at bus stops and the like, and the police pick them up and send them to government homes. And they contact Chora Chori and they come to pick them up. Chora Chori has developed such good relationships with authorities in India that they are able to do this despite the fact that nobody has papers, and they don’t know how old the children are. It’s dangerous as well. You’re dealing with abuse, but you can’t confront them. And it’s hard, because there are Indian children begging to be taken to Nepal. It’s heartbreaking.

What’s UiH’s role in this?

Chora Chori bring the children back to Nepal and try to reunite them with their families. There’s also a refuge centre, which provides some form of clinical emotional support to the children. So we support the psychologists because they are dealing with very complex issues.

Parents have legal authority over the children, so when they return to their community, they face the risk of being sold again. UiH supports Chora Chori by setting up a team to visit the children at their homes and provide follow-up care to them.

What difficulties do you face when raising funds for your cause?

What we do is pretty intangible. It’s very hard to chart, record or measure the work we do. It’s behind the scenes and is somewhat related to how international development happens. Funders tend to go for tangible results and the sustainability aspect of international development keeps getting postponed, which is, quite simply, investment in people. And in our case; a local healthcare workforce.

From the UiH fundraiser on 17 Nov 2018.

Your recent fundraiser in Singapore was held with the aim of procuring a jeep to help with transportation issues. Was that successful? Other than donations, how else can people help?

At the moment, when we travel, we rent a jeep and a driver and it takes up to half of our budget when we go on an outreach. Chora Chori also need a vehicle, so rather than having both organisations look for a jeep, UiH will get one and we can both share the jeep. Right now, Chora Chori takes public transport to retrieve the children. Two staff members with seven or eight kids on a bus over two to three days!

The sheer distance between places is a very practical issue that affects people everywhere. And we feel that all these funds are being wasted on transport. Besides, people want to associate giving with something, so a jeep is very tangible.

At a training programme by Unity in Health for the nursing staff of the Nepal Medical College