A Straight Line in the Sand: Thoughts on A Land Imagined

by Marc Nair, 10 March 2019

A Land Imagined, Yeo Siew Hua’s second feature film, slips in between genres, wearing a particular hue that isn’t often seen in Singapore. Winning the Golden Leopard at the 2018 Locarno International Film Festival, Yeo has joined the likes of Preminger, Jarmusch and Kubrick in scooping up this prestigious award.

Here’s the plot in brief: A worker from China, Wang Bi Cheng (Liu Xiaoyi), who’s on light duties after breaking his arm, goes missing together with the lorry he’s driving at a Singapore land reclamation site. Detective Lok (Peter Yu), an insomniac police investigator, and his sidekick are assigned to unravel the events that led to his disappearance, discovering a seedy underbelly to the country, miles away from the Crazy Rich Asians landscape preferred by the Singapore Tourism Board.

The mise en scène of the film is built around rare glimpses of actual worker dormitories and construction sites, usually off-limits to the public. Yeo was able to get access to these spaces because he had a locations team that pushed hard for access to some of these highly restricted locations.

Yeo: It was absolutely crucial that we captured the real living and working conditions of the migrant workers. It was just not possible to build a set for it. I was adamant on approaching this film with elements of the real, a bit like a documentary.

This blend between a fictive plot – in itself sparked by the real life protest of a pair of crane workers in 2013, and everyday scenes unsettles the audience. The scenario is a plausible one and it plucks at our collective conscience. So much of how Singapore is built is unseen. Citizens throw up their own social walls, separating migrant workers from the rest of the country. Even the intersection points in the film are liminal spaces; the cyber café with Mindy (Luna Kwok) the night manager/hostess and the man-made beaches made from sand imported from various countries: Indonesia, Vietnam, Myanmar, etc. Wang jokes about taking Mindy to a different country every night.

William Jamieson writes here of the irony of reclamation, which “appears to imply that Singapore is retrieving something from the sea, re-claiming what was already its own, when it has in fact been building land where land had never existed before.” And in Yeo’s film, the unsaid looms larger than life on our screens, piles of sand that could hide anything; even a body. At what point does Singapore stop being Singapore?

The film offers insights into identity formation through contemplative, sometimes cryptic lines like what Lok utters when Jason, the nephew of a construction company boss, takes him to see an island of reclaimed sand.

Lok: What is this land that we can shape and mould as we please?

Jason: Officer, your question is too deep for me. I hear you but I don’t understand.

Yeo: Identity formation in Singapore is fluid and schizophrenic. Like our ceaselessly shifting shorelines, (re)claimed from sand we appropriate from so many places, our cultural make up is just as layered but also imaginary and political because it is not an organic formation, but imagined and designed through policy.

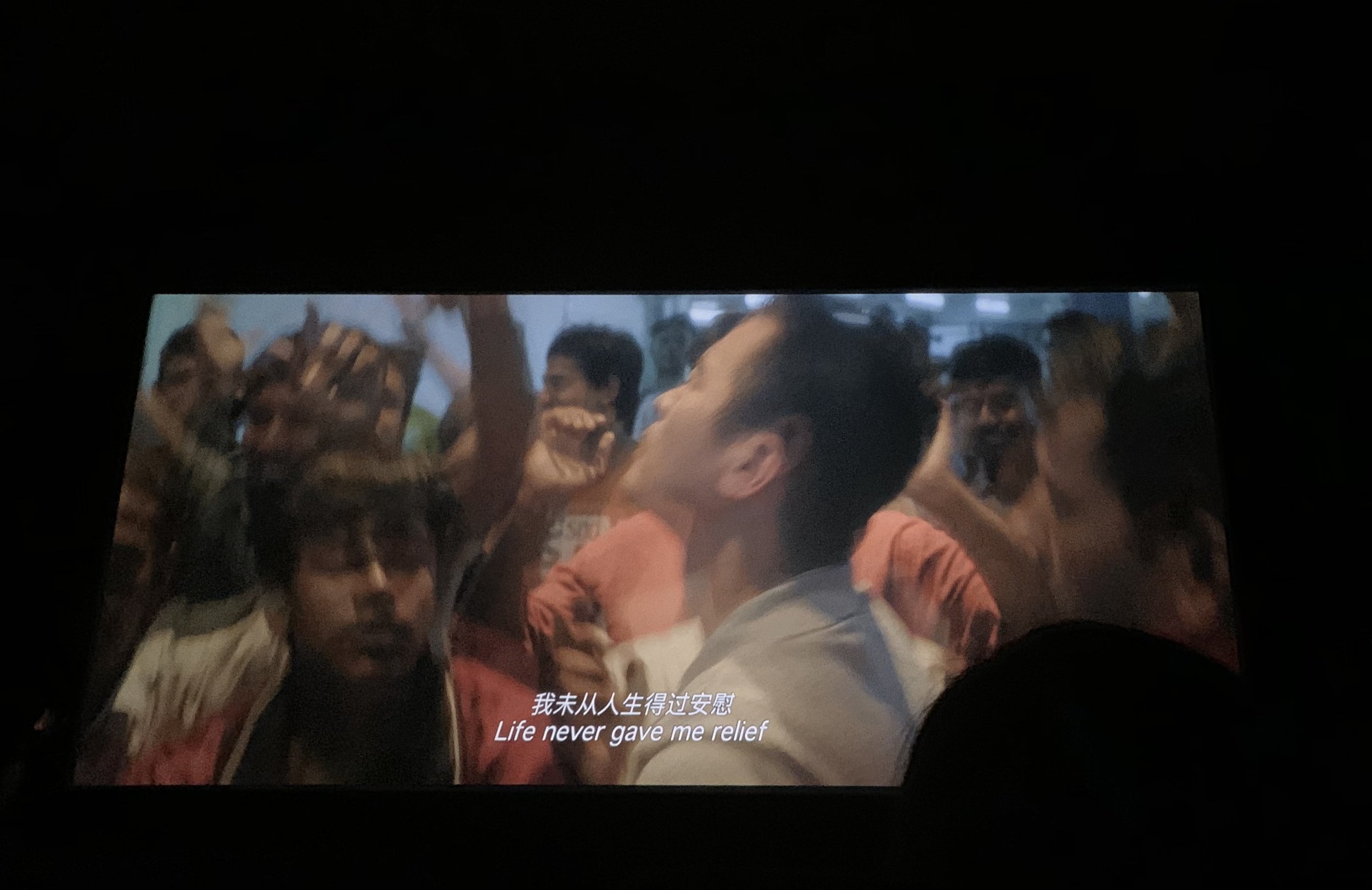

The polity of Singaporeans, who define identity through National Day songs, is an implied parallel to the wrenching tunes sung and danced by the Indian workers in the evenings; dances in which first, Wang, and then later, Lok join in.

Photo by Mackerel.